|

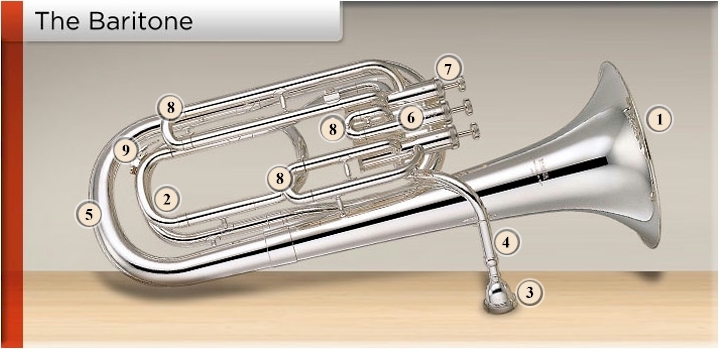

PARTS OF THE BARITONE HORN

|

| Ref No. | Description |

| 1 | FingerTip |

| 2 | Felt |

| 3 | Top Cap |

| 4 | Stem |

| 5 | Guide |

| 6 | 1st Valve Piston |

| 6 | 2nd Valve Piston |

| 6 | 3rd Valve Piston |

| 7 | Valve Spring |

| 8 | Bottom Cap |

| 9 | Bell |

| 10 | Mouthpipe |

| 11 | Levers |

|

| Ref No. | Description |

| 12 | Mouthpipe Brace |

| 13 | Branch |

| 14 | Guard |

| 15 | Bell Brace |

| 16 | Thumb Hook |

| 17 | Lyre Holder |

| 18 | Lyre Holder Screw |

| A | Tuning Slide Complete |

| A1 | Waterkey Assembly** |

| B | 1st Slide Complete |

| B1 | Slide Knob |

| C | 2nd Slide Complete |

|

| Ref No. | Description |

| C1 | Slide Knob |

| D | 3rd Slide Complete |

| D1 | Slide Knob |

| ** | Waterkey Assembly (A1) |

| W (a) | Waterkey |

| W (b) | Cork |

| W (c) | Bumper |

| W (d) | Screw |

| W (e) | Spring |

| W (f) | Bridge |

| W (g) | Nipple |

|

* From http://www.kanstul.com/parts-baritone-390/

|

ANATOMY of the

BARITONE HORN*

Baritone horns are powerful brass instruments that produce some of the lowest tones heard in a jazz band and orchestra.

The baritone is pitched in Bb, like the euphonium and the tenor trombone, and is in the lowest brass register in the orchestra (where it is typically used in the place of the trombone). The baritone's full musical range begins at approximately E on the line below the bass clef staff to the C above the treble clef staff. Its cylindrical tubing would measure about nine feet if laid out in one straight line.

To be the best you can be at playing the baritone horn, you should know all of the usual names of the parts of the baritone and what function they perform. You should also know how individual baritone parts can be removed and replaced, how baritone parts should be serviced and maintained and what to do if you think a part of your student baritone horn is damaged or broken.

Many people use the terms "euphonium" and "baritone" interchangeably, though this is incorrect. The two instruments look alike and have similar function, but the euphonium usually has an extra valve and a larger bore that gently tapers out to the bell. The baritone always has three valves and a smaller bore. British models tend to have the bell pointing directly overhead, while American versions have a bell that aims forward at a slight angle.

As a result of the variation in bore, these two instruments have a slightly different sound as well. The baritone has a sharper, more distinct sound and the euphonium has a rounder, less aggressive tone.

Let's learn about the anatomy of a typical baritone from end to end. If you'd like to jump ahead, use the anatomy chart above to click a part you'd like to read about first.

1. WHAT IS THE BELL?

The bell is where sound waves emerge from the baritone's nine foot length of tubing.

The horn of a baritone is highly polished and tapered out generously to spread the sound waves widely. The sound of the horn, produced from the lips of the player and shaped through the horn, comes to powerful fruition at the bell with volume and clarity.

Care must be taken never to set your baritone horn down on the bell, either flat or on the side. This is true even on a carpeted surface. The highly polished surface scratches surprisingly easily and a horn balanced on the floor is a recipe for an accident and a bent horn. Every inch in the shape of the horn is designed to produce the best tone and volume, so even a slight change in the shape of the metal can affect the sound profoundly. Be sure to store the baritone safely in its case when it is not in your hands or place it on an instrument stand designed specifically for baritone horns.

The bell and all the metal of the instrument can be polished gently with a soft lint-free cloth to remove dirt, dust and fingerprints. Be sure to remove any dirt from the instrument immediately after each playing session, as it can very quickly degrade the finish of the instrument if left there.

2. WHAT IS THE MAIN TUNING SLIDE?

The main tuning slide is used to make micro-tuning adjustments to the baritone.

The main tuning slide can be moved in and out with a small amount of pressure, allowing the player to make micro adjustments to the tuning as needed on the fly. The water key is located on one corner of the tuning slide, so the player can gently blow out moisture that might have collected in the baritone.

3. WHAT IS THE MOUTHPIECE?

The baritone's oversized, deeply cupped mouthpiece directs air and lip vibrations from the player into the body of the instrument.

The baritone's mouthpiece is deeper even than the trombone's sizable mouthpiece, and for this reason many players find the baritone to be one of the easiest brass instruments to produce a tone on even as a beginner.

4. WHAT IS THE MOUTHPIECE RECEIVER?

The mouthpiece receiver connects the mouthpiece to the baritone.

The mouthpiece receiver is a small metal cylinder fused to the end of the leadpipe that connects the mouthpiece to the baritone. The mouthpiece, which is removable, is gently pressed into the leadpipe before playing and taken out for cleaning and storage after playing.

Be sure not to apply too much pressure when placing the mouthpiece into the baritone mouthpiece receiver, as the mouthpiece could get stuck or damage the mouthpiece receiver. If your mouthpiece gets stuck, do not try to remove it yourself. Take the baritone in for repair.

5. WHAT IS THE TUBING?

The baritone has roughly nine feet of tubing to carry the sound waves from mouthpiece to bell.

The baritone's tubing is generally made of brass and has a length of approximately nine feet from end to end. The tubing is cylindrical, rather than conical like the euphonium.

Sound waves originate from the mouthpiece and vibrate inside the tubing to produce varying tones. The player's mouth (in the mouthpiece) and hands (depressing the valve pistons) work in combination to play each tone. The tubing ends with a flourish at the bell.

Every inch in the shape of the horn is designed to produce the best tone and volume, so even a slight change in the shape of the metal can affect the sound profoundly. Be sure to store the baritone safely in its case when it is not in your hands or place it on an instrument stand designed specifically for baritone horns. Otherwise, one second of distraction and a carelessly stepping band member could mean even severe damage to the horn.

6. WHAT ARE THE VALVE CASINGS?

The valve casings are cylindrical metal tubes that hold the pistons as they move up and down.

As the player depresses a valve piston, it slides down in the casing to match up the holes it has with holes in the casing that lead to different slides. The changes to the total tubing length that the air and sound waves pass through via these holes creates the different notes of the chromatic scale.

The valve casings can be lightly lubricated with a very thin coat of valve oil. Be careful not to overoil your valve casings, or you will have a bit of a mess on your hands as it drains out the end of the casing.

7. WHAT ARE THE VALVE PISTONS?

The valve pistons move up and down inside the casings, changing the length of the tubing and the tone that is produced.

The player uses the fingers to depress the valve pistons in various patterns, which changes the air path inside the baritone slightly to produce a different tone. Each piston has holes that pierce through it, so as the piston slides down inside the casing the flow of air is changed. While each piston has only an official up and down position, some players have experimented with depressing the pistons only part way to produce different sound effects and notes from the instrument.

The valve pistons can be cleaned with a soft, lint-free cloth and lightly treated with valve oil to keep them functioning in top shape. Be sure to inspect them regularly to avoid having grit scratch the piston.

Note that if you remove a piston from a casing it is imperative to place each piston back into the proper casing for the horn to function properly. If a valve piston gets stuck for any reason, take it to an expert instrument technician to fix it. Forcing the valve piston could result in bending or scratching it.

8. WHAT ARE THE VALVE SLIDES?

The valve slides allow the baritone to produce different tones by changing the overall length of the baritone's tubing.

There are three valve slides on the baritone, the first valve slide, second valve slide and third valve slide. The first slide is closest to the mouthpiece. Each is placed at a precise point in the flow of air inside the instrument to allow the baritone player to change pitch by depressing pistons while playing or make micro-adjustments to the tuning of the baritone by moving the slides in and out. The slides are fitted tightly so they hold their position by themselves but can still be moved in and out with a small effort.

The valve slides should be removed and cleaned periodically and lubricant reapplied. Note that the grease used for slides should never be used with the valve pistons. If the valve slides become stuck, do not attempt to force them loose. Take the baritone to a technician for service.

9. WHAT IS THE WATER KEY?

The water key allows the player to quickly remove moisture from the horn's interior.

The water key is a small metal lever usually found on the baritone horn's main tuning slide that can be pressed to open a small hole in the slide and allow water to escape. During a playing session, it is common for small amounts of water to collect in the slide. This moisture can be removed in short order by pressing the key and blowing sharply into the mouthpiece.

The water key has a small felt disc on the end to help seal the hole when the water key is closed. Take a look at the disc on occasion to make sure it is still clean and providing a good seal. You don't want dirt or mold to collect anywhere on your baritone. If the disc appears to need replacement, take it to be serviced.

* the above taken from https://www.theinstrumentplace.com/parts-of-the-baritone-horn

|